I should be more consistent with writing. I don’t usually sit down and think of a particular topic to write about. Most of the time, it just comes to me. Just the other day, I was thinking about “failure.” I realized that many things I write about have failure as a central theme. I don’t consider myself an expert on anything, but if I were to bestow that title on myself in some regard, it would be “Master of Failing.”

To be honest, I’m not even mad about it. It took a while to learn, but once I figured out that failing was an important part of growing, I decided to embrace it. I’m not saying that I have never made the same mistake twice, but I feel like most of my failures are unique, and I use them to fuel growth and development.

I’ve been in the car business for almost 20 years. When you are a professional salesperson, failure is a constant factor. Even the best in the industry don’t sell to every customer they talk to. A GOOD salesperson should expect to close 30%- 35% of the customers they interact with. To put it in perspective, if a baseball player gets a hit one out of every three times he goes to the plate, he’s considered a Hall of Famer. Similarly, if a salesperson closes a sale with one out of every three customers, they’re doing exceptionally well.

That means that the best players in the game’s history fail two out of every three times they have an at-bat.

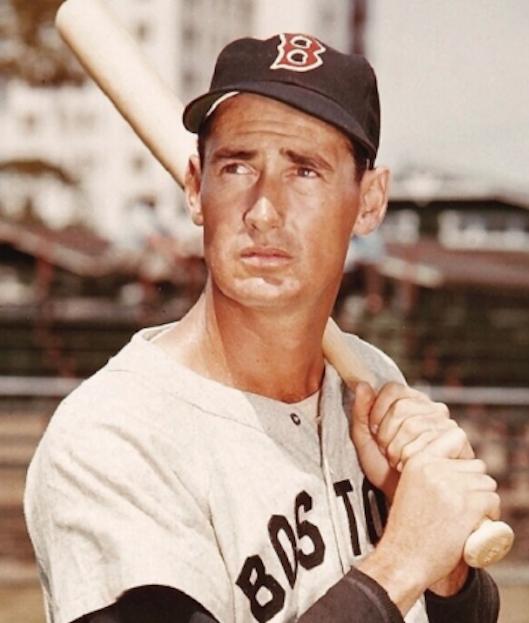

Today, I’m returning to 1941, when Ted Williams had arguably the best season at the plate in baseball history. He finished the ’41 season with a batting average of .406 with 37 home runs and 120 RBIs. To provide context, .200, the Mendoza line, is considered the low-end threshold for professional ball players. The average batting average of Hall of Famers is .303.

Williams played in 143 games that season and had 456 at-bats. But the breakdown of three particular stretches of that 1941 season interests me the most.

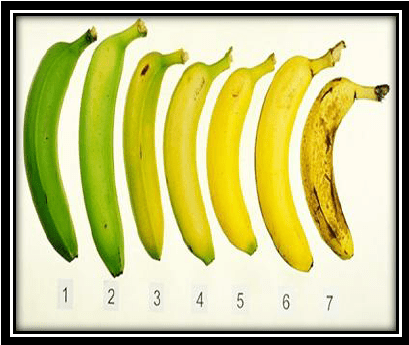

On April 30th, Williams entered the game hitting .462. Over the next four games, he hit .182, dropping his season average to .310.

By June 21st, he had battled his way back up to .415. But he only hit .318 over the next 21 games, dropping that average all the way down to .393.

His average peaked again at .413 during the heat of the pennant race in early September. But a .292 stretch over the next 17 games saw it drop right to the .400 mark near the end of the season. Entering the last day of the year, he was so close to the .400 mark that a bad day at the plate would have kept him from reaching that sacred number.

This is important because even though his season as a whole is considered extraordinary, not every day, or even week, was even considered average. But during those subpar stretches, Ted Williams didn’t panic. He didn’t change up his swing. He didn’t stay down in the dumps and stop coming to work. He showed up every day, stepped inside that chalk-outlined box, and did his job to the best of his abilities. And he let the chips fall where they may.

The most significant lesson I’ve learned about failure is that it’s interwoven into the fabric of success. It’s more about ‘fall, learn, grow’ than ‘pass or fail.’ These three unremarkable stretches of Ted Williams’ historic season wouldn’t impress anyone. But his resilience and determination during those times are just as, if not more, important than his successes.

We get so caught up in results that sometimes we lose focus on the processes. Instead of getting up and walking out of the pit of despair, we let ourselves get so deep that we can’t even climb out. We let our losses define us even though we may be on the cusp of a breakthrough. Our inactivity lets the tide sweep us back to the starting line when riding the wave will get us closer to our destination.

I used to tell kids when they’d ask me a question, “I wish I had it all figured out.” I don’t tell them that anymore because it isn’t true. I’m glad I don’t have it all figured out. My next failure is always right around the corner, and I’m excited to see what revelation it will lead to. I try (emphasis on “try” ) to be consistent and open-minded while keeping a positive attitude. In the words of the great poet Henry Longfellow: “Learn to labor and to wait.”

Show up. Stay the course. Keep your head high. Learn. Don’t quit. Don’t ever quit.